Black Roots: 'The youth will always relate to the message of roots reggae'

Posted on: 21 Dec 2019This article was first published in LOUD Magazine Issue One, released in November 2019.

Rigs in the streets, balloons and bottles in hand, thousands of ravers block the roads and dance while police look on, docile. It’s the loose landscape we’ve all become accustomed to in Bristol, but it never used to be like this. The sound of the city as we know it is rooted in a pioneering soundsystem culture, cultivated by Bristol's West Indian community in the late 1970s and early 80s.

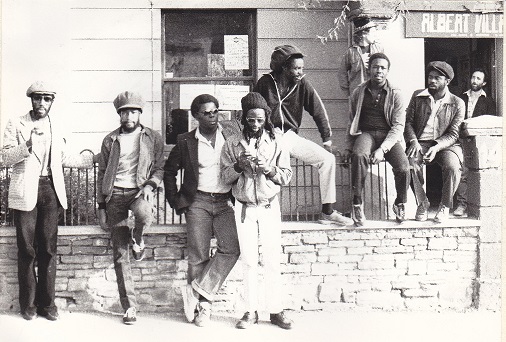

Black Roots are one of the most well-known roots reggae bands to have ever come out of the UK, let alone Bristol. Originally formed with ten band members, today I sit down with four, Jabulani Ngozi, Kondwani Ngozi, Carlton Smith and Errol Brown.

Jabulani Ngozi, Kondwani Ngozi, Carlton Smith and Errol Brown of Black Roots. Image: Jono Leach

Jabulani Ngozi, Kondwani Ngozi, Carlton Smith and Errol Brown of Black Roots. Image: Jono Leach

We meet at a sombre time, with the news that original founding member Charlie has sadly passed on the day of our interview. The band are in shock, but still want to share their story, “Charlie was our brother” they say. “Charlie had those ancient reggae vibes, which he put out physically in his energy and his voice” Jabulani explains, in his strong, commanding tone.

As the youngest member of the band, Carlton poignantly shares a memory of him as a teenager standing front row at the early Black Roots shows. “I used to watch Charlie and he made me love the music and want to do it. I’d go home and practice for hours, and then I ended up joining the band!” he smiles.

The band’s energy is a strong presence in the room and commands a sort of calm respect. “We got nothing to prove,” Jabulani points out, and it’s evident. Kondwani picks up an apple from the fruit bowl in front of him, and leans back into his chair tranquilly, dropping regular words of wisdom throughout the duration of our interview.

This year marks Black Roots’ 40th anniversary, but let’s go back for a minute. Imagine the year is 1965, a group of youths emigrate from Jamaica to the cold and unwelcoming streets of Bristol. “It was very hard for us because many places didn’t accept or accommodate you. Really and truly all our lives we had to fight some form of racism.” Jabulani tells me, recalling the socio-political landscape of Bristol, and indeed the rest of the UK, at that time.

Black Roots in St Paul's, circa 1980. Image: Black Roots Archive

Black Roots in St Paul's, circa 1980. Image: Black Roots Archive

Growing up, the band were experiencing the early days of soundsystem culture in all its rebellious glory, bringing the heavy bass music to the streets of England, in a powerful movement the likes of which had never been seen before. St Paul’s became the musical hub of the city - soundsystems were owned by the West Indian community, and those who previously didn’t have a platform to put their sound to the test, now could.

Fast forward to the year 1979 and the same youths, now young adults, are playing dominos in a basement “in a place just like this” Jabulani remarks while looking around the room we’re sat in today. It was in that basement that Black Roots was born. From a lack of opportunities, they wanted to try to make something for themselves, like they were witnessing their elders doing.

“After seeing Burning Spear at Colston Hall our brother Charlie had the idea to form a band,” Carlton explains. At that time, soundsystem culture had boomed into a fully-fledged “enterprise,” and it had taken over the underground soundscape of the city.

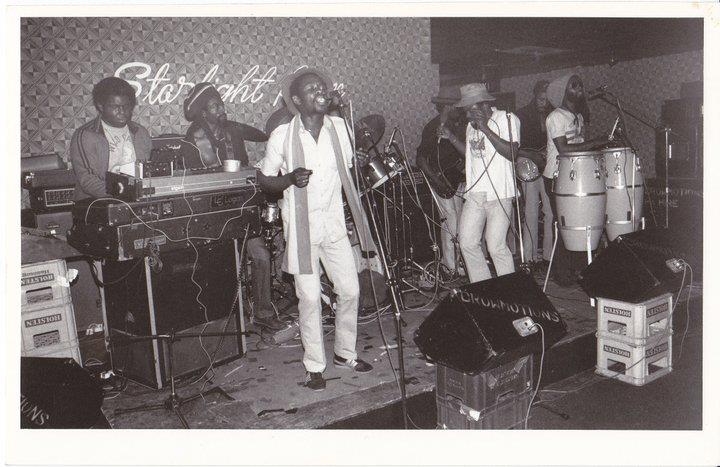

Black Roots on stage at The Starlight Rooms in London, 1981. Image: Black Roots Archive

Black Roots on stage at The Starlight Rooms in London, 1981. Image: Black Roots Archive

“We started coming up with cash to build soundsystems so we could put our music out ourselves,” he says. In the days before they would gain international traction, Black Roots - like many other black musicians living in an environment so deeply ingrained in racism - had to accommodate their own spaces to play, “the blues parties as we liked to call them,” Jabulani remembers.

These blues parties were organised house parties which were happening all over the country in basements and backyards. People would bring their own soundsystems and, in some cases, charge an entry fee on the door. “It was like setting up a company, a business - everyone had their jobs to do, you had a manager, a selector, a sound engineer, an MC," Carlton remembers. "The best sounds that made it were the most organised."

These parties marked a pivotal moment in UK culture, genuinely instrumental in breaking down racial and social barriers at the time, as Jabulani explains: “the European youths started to come and see our music and see what we were about, so they participated in what we were doing and that’s when we all started to integrate.” The band played alongside some well-known soundsystems including Tarzan the High Priest, Count Ajax, Commander, Still Water and many more.

“If anyone tells you that there's no such thing as good British reggae, first tell them they’re a herbert, then show them Black Roots”

- John Peel, 1981

It wasn’t until the 80s that Black Roots would be welcome in clubs and legitimised music venues. They gained a notable following in 1981 after John Peel showcased their debut EP on his show, the revered Radio 1 DJ famously telling his audience “if anyone tells you that there's no such thing as good British reggae, first tell them they’re a herbert, then show them Black Roots.”

In the years that followed, the band toured the UK and Europe playing clubs, venues, college parties and regular festivals like Glastonbury, touring with the likes of UB40, making TV appearances and releasing several successful albums including Black Roots, The Frontline, In Session and more. “Rest in peace John Peel who helped make us,” Jabulani says, “after he showcased us we got tours, doors started opening. Him, Peter Powel and Kid Jenson were the only DJs who played reggae and our music in those days.”

Forced to release material independently from the start, record companies tried to water down their music. “They didn’t want us to play our hardcore roots, they wanted to commercialise it!” Jabulani tells me in frustration. At that time, the best-selling and most heavily listened to reggae music was roots, eventually influencing genres like punk and ska and gaining huge commercial success off the back of the roots movement. Despite all that, though, the band always remained true to themselves and went on to gain a huge worldwide fan base in the years that followed.

Black Roots performing at the notorious Elephant Fayre in Cornwall, 1983. Image: Black Roots Archive

Black Roots performing at the notorious Elephant Fayre in Cornwall, 1983. Image: Black Roots Archive

During the 90s however, “reggae had a bad beating” Jabulani continues, sighing. But after their several-year hiatus, the band had no struggle in creating new material together, the process being just as organic as it was in the 80s. And that’s the thing about roots reggae, it’s timeless. “When the world is still so unjust it’s easy for us to come up with new music”.

After the release of their first studio album in 20 years, On The Ground, back in 2012, the band put out more original recordings. Ghetto Feel came in 2014 and Son of Man followed in 2016, and in 2017 they released Take It on their imprint Nubian Records. The band went on to re-release some of their back catalogue under the new title, With Friends, in April of this year. Black Roots believe that “the youth will always relate to the message of roots reggae," and they show no signs of stopping anytime soon.

Now, the creative flow is strong as ever, although the process is never without creative blocks. Kondwani reassures that when that happens, you have to “listen to your body, trust people and be true to yourself” in a moment of enlightenment. Smiling, Jabulani chimes in “many times you get a block, so what you do? You bun a spliff and walk out in mother nature, and lead yourself back to where you need to.” Even the trees make melodies, the band agrees.

Now, when we think of Bristol and it’s its cultural development throughout the years in music, electronic music takes the helm. A city revered for its raves It’s easy to see how this side of dance music culture may have “squashed reggae” as Carlton suggests. But equally, as Kondwani says “Roots reggae is like a tree with many branches”. He’s absolutely right, it runs into all avenues of modern bass-driven electronic music. It can be traced back to dub, punk, and 90s trip-hop, through to contemporary drum & bass, jungle, dubstep, and even grime.

Today, Bristol’s bass scene is larger than ever, soundsystem culture sculpted the city’s soundscape as we now know it, with the 140 bpm dominating a large part of the spectrum. “I’m starting to really like grime,” Jabulani smiles, while the others nod in approval. In fact, Carlton’s son and Jabulani’s grandson make grime, exemplifying the music’s development between generations. There are certain similarities between roots reggae and grime, in that both genres can lyricise social issues and have a political underbelly.

Carlton remarks how his “kids go to drum & bass raves, where a lot of reggae is pirated and mixed into sets! And they still always ask when we’ve got new music coming!” In proof that the message of roots music remains everlasting. “What we say, in our lyrics,” - talking of the political reference in ‘Take It’ of the Tories as false prophets and Trump as a reincarnation of Hitler - “everybody’s thinking already."

As part of their 40th Anniversary celebrations, Black Roots have reissued their 1993 album, With Friends, available now to buy and stream via Nubian Records. Find out more on the official Black Roots website.

Header Image: Jono Leach

Read more:

-

LOUD Issue 1: 'The best is yet to come' | A word with Mix Nights' Lizzy Ellis

Article by:

Hannah recently graduated with a degree in English with Writing. She is an avid writer, freelancer and creative. She is currently writing her first full-length novel and a collection of poetry. Always out and about in Bristol's music scene, she attends music events on a weekly basis.