The Sound of Bristol: IDLES

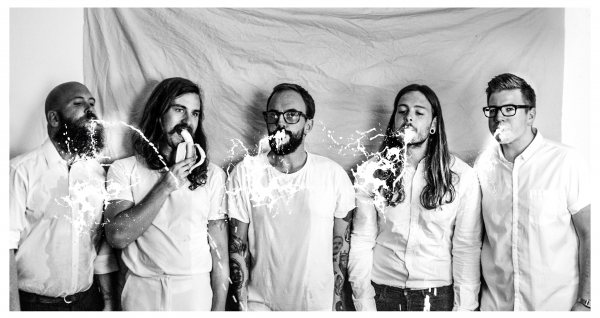

Posted on: 24 Oct 2016As the debut of the new series The Sound of Bristol, which examines the eclectic reaches of the city's music in weekly instalments, we sit down with inflammatory five-piece IDLES, who have led a resurgence of sorts in millenial post-punk sensibility.

The noise peddled by IDLES, by their own admission, is anything but standstill. “The basis for our music is a very heavy, motoric bass and rhythm section, and then quite strange, mechanical sounding, abrasive guitars. And then me on top,” grins Joe Talbot (pictured, centre), the surprisingly softly-spoken frontman of the Bristol five-piece who play, in his words, “heavy post-punk”.

Talbot goes on to coin his genre as ‘recession soul’, a term which finds its origins in a conversation he shared with a friend about synaesthesia - an inter-sensory condition in which music is able to be seen as a colour. “We were talking about how things seem similar, and I’ve always said that the closest thing to punk, either before or after it, is soul music because it has a similar aura, colour, essence to it; they feel the same,” he explains. “If you listen to second album Iceage and put it next to a Lee Moses track like ‘Bad Girl’, it has the same real, visceral, guttural feeling of angst and pain and unabashed passion that you don’t get with other genres.”

With a crooked smile adorned by a pair of round reading specs and a knitted jumper not quite hiding the tattoos which creep up his neck, here Talbot appears very much the polished, public face of one of the country’s most snarlingly truculent bands. Going on to discuss his penchant for the novels of James Baldwin and Cormac McCarthy, and his day job as a support-worker for adults with learning difficulties, this doesn’t sound like the man who regularly spits lyrics as pugnacious as “I’ve dreamed about burying you in a forest / If I were you I wouldn’t wait for the chorus.”

He does, however, appear visibly miffed when the bearded bassist, Adam ‘Dev’ Devonshire (pictured, far right), sitting to his right, interjects to add, “Both punk and soul come from the same place politically.”

“No, politics is more of a subject, I’m talking about a pure sound and a feeling,” comes the rebuttal. “It’s the passion and drive behind those genres. I wanted to get away from the idea that it was soul music in any sense of that word, but instead something from the soul that’s low-budget, with no glamour. It’s basically what a lot of people would say punk music is. There was a recession going on when I said it, so it’s about being the voice of a generation or a time, with passion and love and anger. Like soul music did.”

With the caustic quality of Talbot’s time-sharpened tongue readily attested to in the songs which leave social commentary behind for abject social criticism, it is perhaps inevitable that it swiftly turns itself towards the modern political landscape: “At this present time there is a feeling of unrest. Politics is polarised; the right are a lot more right and the left are a lot more left than they were five years ago.”

“It’s an interesting time for people like us, who are f****d off. But I’ve been f****d off for 20 years. We’re a very angry band,” the tirade continues. “We’re very p****d off with the country, I’ve hated a lot of things, but now it’s more palatable because everyone is pissed off. We’ve been shouting for a while and now people are joining in.”

Asked about the impact of politics on music, Talbot expounds a co-dependent relationship which comes dangerously close to agreeing with what his bassist had said earlier: “I think people are fickle. I think there is this cyclical nature of dance music and then punk music and then dance music and then punk music, according to the social movement of the time. Guitars, synths, guitars, synths - one goes up while the other goes down. In a recession, anybody can pick up a guitar - that’s not a new idea. If I wanted to make a punk song, I could go and get an electric guitar, plug it in, write a few songs, then go to a night and play it.”

Electronic music, “that extravagant, jubilatory feeling of euphoric-sounding music”, Talbot posits, is of an altogether separate time and mood. “Dance music happens when everyone has cash to spend, everyone is having fun. It’s all nice, it’s all blooming ciders in the park. And then when’s there’s a recession, all of a sudden it’s ciders in the car park. It’s a different kind of cider and it’s a different kind of attitude.”

At present, if this theory is to be taken as true, we sit at the eye of this enormous and ever-turning cyclone, at the silent calm between the perpetual ebb and flow. “People will never get bored of guitars, they’ll only get bored of a certain way in which guitars are played,” he continues. “Now, we’re in that interim period at the moment, I think it’s a free-for-all. I don’t think anything has really got the nation by the ovaries.”

To continue with this metaphor of procreation, Bristol in particular, of late, has seemed like a fertile breeding place for good, young bands coming through the ranks and going from strength to strength. Despite this, the idea of the city as playing host to a ‘scene’ has never sat easily with IDLES, with their track ‘Imagined Communities’ expressing the dangers of succumbing to localised tribalism.

The singer explains that their early attempts to include other local musicians gained them friends, but didn’t lead to the creation of a larger network. “It helped us enjoy it more because it meant that we got to play with loads of other cool bands. We’re friendly, we’re amiable guys - I think; it depends how much we’ve drank,” he smirks. “But there was no scene. There were good bands, but it was all quite standoffish.”

According to Talbot, it is to the diligent work of Howling Owl, the distinguished Bristol label, that the city owes the plaudits to its fledgling scene. “We wanted to make friends, they wanted to make an actual infrastructure that made the city better musically and they did. And now there’s a whole network of people who are in contact and get on well with each other.”

“Places like the Stag and Hounds are a very important, integral part of the city, especially now Start The Bus has gone,” Dev pipes up. “They put on literally everyone, everyone who struggles to get a gig elsewhere and do a very, very good job.”

The closure of Start The Bus (which the bassist refers to as “A nail in the coffin for young bands who are unable to get exposure in other cities”, having played the venue several times, below) is a major setback to the city’s musical output and infrastructure, which had seemed to be flourishing exponentially up until that point.

The news will mark a sad footnote on this weekend’s frivolities, which will see a full-scale celebration of the city’s noises when Simple Things takes over town. Talbot makes no effort to disguise his excitement for the festival, which he describes as “as good as it gets.”

“I love everything about it. It’s run by really passionate, intelligent, great people,” allowing himself a rare moment of unabashed gushing. “The guys who run Crack magazine are great, really hardworking, honest guys - it’s not pretentious in any way, they’re just good hardworking people. I’m just glad that there’s this kind of stuff going on, as you don’t have to be annoyed about loving it because they’re not up themselves.”

As he reels off the reams of bands he is looking forward to checking out over the weekend, among established mainstays like Warpaint, Death Grips and Suuns, he counts Bristol newcomers LICE, Rink and Bad Sounds. The glint in Talbot’s eye as he does so seems to suggest that it is as a result of this new glut of bands, kicked into action by the music of the man himself, that the nation should fear most for her ovaries.

Article by:

An ardent Geordie minus the accent, Sam seemingly strove to get as far away from the Toon as possible, as soon as university beckoned. Three undergraduate years at UoB were more than ample time for Bristol (as it inevitably does) to get under his skin, and so here he remains: reporting, as Assistant Editor, on the cultural happenings which so infatuated him with the city. Catch him at sam@365bristol.com.